From the end of the 19th century, scholars have been searching for the origin of the Greek Aphrodite, the goddess of love. For some, she was a blond goddess from the North, of Indo-European origin. For others, she came from the Orient. But for the Ancient Greeks she was the goddess of Cyprus, born from the foam of the sea and worshipped in Paphos. References in ancient authors and archaeological evidence may prove that Aphrodite originated in Cyprus.1

Sources in ancient texts

Homer (9th-8th centuries BC) refers to Aphrodite as Kypris, especially in the Iliad 5.330-342, 347-362, 418-430, 454-459, 755-761. He mentions (Odyssey 8.360-366) Aphrodite’s sacred precinct in Paphos with an altar fragrant with incense, where she went to be bathed, anointed with immortal oil and clothed in lovely garments by the Graces.

Homeric Hymn 5.53-57 (8th-6th centuries BC) provides the same information as the Odyssey. Homeric Hymn 6.1-18 tells of Aphrodite as the mistress of the walled cities of the island of Cyprus and narrates that she was brought by the wind zephyr over the waves of the sea in soft foam and welcomed by the Hours who dressed her in heavenly garments, adorned her with golden jewellery and took her to the gods.

Homeric Hymn 10.1-6 refers to Aphrodite born in Cyprus as the queen of well-built Salamis and sea-girt Cyprus, who gives kindly presents to men.

In Asia Minor, in the 9th-8th centuries BC, Homer knew of Aphrodite as the goddess of Cyprus and of her sanctuary which actually existed in Paphos. Aphrodite was still unknown in mainland Greece where her cult is not witnessed before the 7th century BC.

Hesiod, a Theban poet (8th-7th centuries BC), narrates the strange birth of Aphrodite (Theogony 176-206): Aphrodite was born soon after the creation of the world, at a time when the first gods Gaia (Earth) and Uranus (Heaven) procreated at random. Gaia rebelled against Uranus because she was suffocated under all the creatures he had forced her to procreate. One of their sons, Cronus, accepted to mutilate Uranus. Uranus’ genital parts fell into the sea where they created foam from where a maiden was formed and taken by the waves first to Cythera, then to sea-girt Cyprus. Thence she went to the assembly of Gods accompanied by Eros and Desire.

Herodotus (5th century BC) says (History 1.195.2-3) that the temple of Aphrodite in Cyprus was founded from the temple of Aphrodite Ourania in Ascalon in Syria-Palestine, which was the oldest of all temples of the goddess. He also mentions (History 1.199) the practice of sacred prostitution in Cyprus.

Tacitus (1st-2nd centuries AD) reports (Histories 2.3.1) that according to a very ancient tradition, the temple of Aphrodite in Paphos was founded by King Aerias, or by Kinyras, according to a more recent source, and that the goddess landed there after she sprang from the sea. He mentions that at the time of Titus, priesthood and divination were still practiced by a descendant of Kinyras and that the goddess was still venerated in the shape of a conical stone.

According to Pausanias (2nd century AD) (Description of Greece 8.5.2-3), Agapenor, leader of the Arcadians on their way back from the Trojan War, was overtaken by a storm, landed in Paphos and founded the city and temple of Aphrodite.

Many other references have been made to the cult of Aphrodite in Cyprus by later historians and scholiasts. The comments by scholiasts of the first centuries AD are very critical of the orgiastic cult of the goddess.

The genesis of Aphrodite in Cyprus

From these ancient sources and archaeological evidence (numerous stone statues and clay figurines, as well as archaeological remains of sanctuaries and temples), we may try to reconstruct the genesis of Aphrodite in Cyprus.

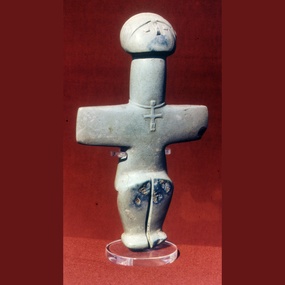

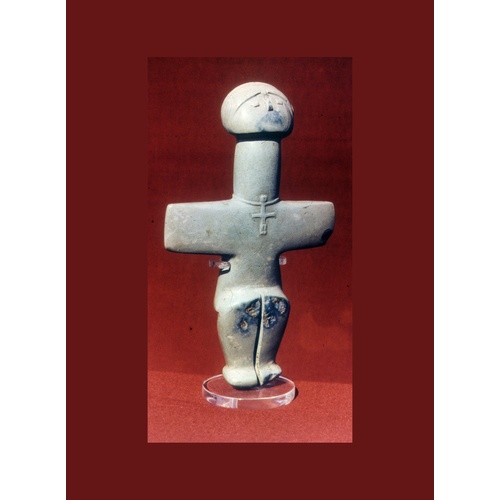

Around 3000 BC, a cult of female fertility developed intensively in the region of Paphos (Kouklia-Vathyrkakas, Lemba, Kissonerga). Limestone, picrolite and clay figurines [Fig. 1] found in tombs and settlements, of an earlier date than the Cycladic idols, represent birth-giving women of different sizes (from circa 2 to 40 cm high) in a cruciform shape. It is certain that a cult of female fertility was flourishing for a few hundred years in the western region of Cyprus. It was centered on the protection of childbirth, which was very important in small societies at a time when infant mortality was very high. But it is risky to assure that a goddess of fertility was already worshipped.2 Later this cult faded away, but may have weakly survived in the western part of the island, leading the way for the establishment of the most celebrated cult place of the goddess of Cyprus at the end of the 2nd millennium BC, exactly in the same area (Palaepaphos).

By the end of the 3rd millennium BC, at the beginning of the Bronze Age, the island was exposed to influences from Anatolia with the settlement of new comers on the north coast. They brought new religious concepts based on the cult of horned animals. This culture produced a hard lustrous ware in the shape of enigmatic plank-shaped figures, found in settlements and tombs, in the north and central part of the island (Lapethos, Vounous, Dhenia, Ayia Paraskevi). They bear incised decoration showing a richly ornamented dress, with jewellery, including earrings in their pierced ears. Some hold an infant, while others have a double head on one single body. It is not clear whether they represent humans or some female deity, but they certainly were cult figures. Representations of infants in their cradles were also placed in tombs. They may have been part of a cult associating a religious idea of prosperity and survival after death with the image of a woman and a child. During the first half of the 2nd millennium BC, these figures developed into clearly defined female figurines with emphasized sexual features, mainly in the central region of Cyprus. It seems that by then some sort of female deity was worshipped.

During the 2nd millennium BC, Cyprus exploited its copper and traded it with countries of the Levant. In consequence, the island was exposed to cultural influences from the Near East. Near Eastern religions in the Bronze Age derived from the older Sumerian Pantheon. The most important goddess in Mesopotamia, characterized by a strong sexual power, was Inanna, which means the Lady of Heaven. Her descendants, Ishtar and Astarte, inherited her sexual features and her overwhelming power over global fertility and prosperity. Their universal nature, their power over kings and men, their fierceness at war, episodes of their existence, such as the sacred marriage with a shepherd king and their descent to the underworld in search of their beloved companion, are referred to in sacred hymns. They were represented by numerous popular idols which have been found at many sites in the Levant.

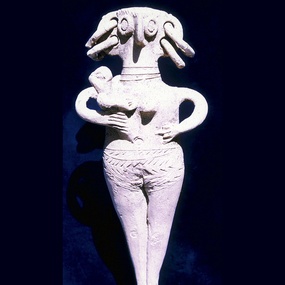

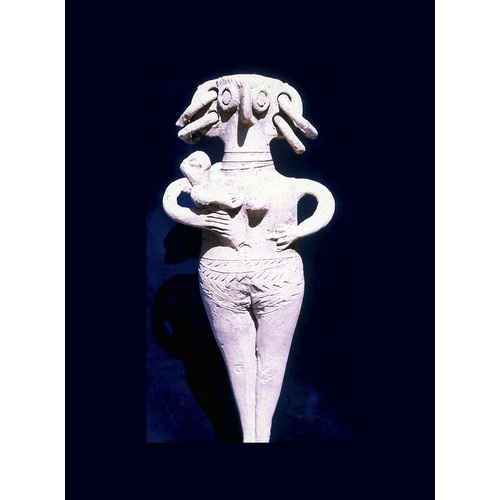

The clay figurines of a new type [Fig. 2], described as bird-faced figurines, which have been found in tombs and settlements of the second part of the 2nd millennium BC, especially in the central and eastern parts of Cyprus, are characterized by their strange head with large perforated ears wearing clay earrings and by their naked body with breasts, wide hips and emphasized pubis. They imitate Syrian prototypes and may have served as charms for fertility, prosperity and protection against death. They testify to the continuity of a fertility cult strengthened by oriental elements and may have been a popular image of some deity. It seems that by the middle of the 2nd millennium BC Cyprus had developed as a wealthy island, whose kings could be compared with the Pharaoh of Egypt and those of the city of Ugarit on the opposite Syrian coast. The island developed its own culture and no doubt its own religious institutions.

Excavations in Kition-Kathari (modern part of Larnaca) have revealed a sacred area along the city wall, with the remains of two sanctuaries of the 13th century BC, consisting of an enclosed courtyard associated with altars, hearths, benches and storerooms. Quantities of copper slag were found in the courtyards and the vicinity. There was a sacred garden between the sanctuaries. Some female terracotta figurines were found on the site. The sanctuaries were probably dedicated to a female deity whose cult was associated with the production of copper and where divination was practiced. These vestiges show an already developed religious context.

Dating to the 13th-12th centuries BC, some bronze statuettes, representing a naked female figure holding her breasts and standing on a base in the form of an oxhide ingot, probably testify to the worship of a goddess patron of copper in different places of Cyprus.

During that period, figurines of the same ceramic fabric as the ones with pierced ears, but of a new style, appeared. They have a normal face without the exaggeratedly large ears and nose, but they are still naked with their hands on their breasts. They show some similarities with Mycenaean figurines, as if Achaean prototypes had begun to alter their characteristic oriental appearance.

At the beginning of the 12th century BC, Kition was reconstructed and fortified with a cyclopean wall. The sacred area was rearranged with four temples, one very large and three smaller ones. Copper workshops communicated with the large temple. Stone "horns of consecration", religious symbols of Aegean origin, stood in the sacred yards. A few figurines of the goddess with upraised arms and some Mycenaean figurines were found, as well as sherds of a new Mycenaean pottery type. The use of ashlar blocks shows a stage of wealth and power. All these changes point to the arrival of Achaean Greeks, who seem to have appropriated holy places and have made them more imposing.

The same situation may have existed in the region of Palaepaphos, which was probably a wealthy region in the second part of the 2nd millennium BC, as shown by the opulence of its tombs. The remains of a sanctuary dated to the 12th century BC have been discovered. It consisted of an open-air sacred yard delimited by a huge, partly preserved wall of massive blocks of stone, and a covered hall on part of one of its sides. Aegean cult elements, such as horns of consecration and stepped capitals, have been also found on the site. The sanctuary bears the mark of an Aegean presence, but it cannot be excluded that a sacred precinct of the sacred enclosure type (of oriental origin?) preexisted on the site.

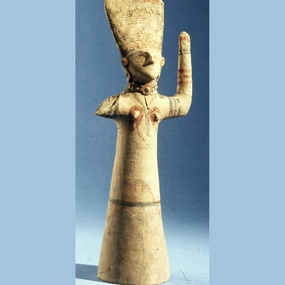

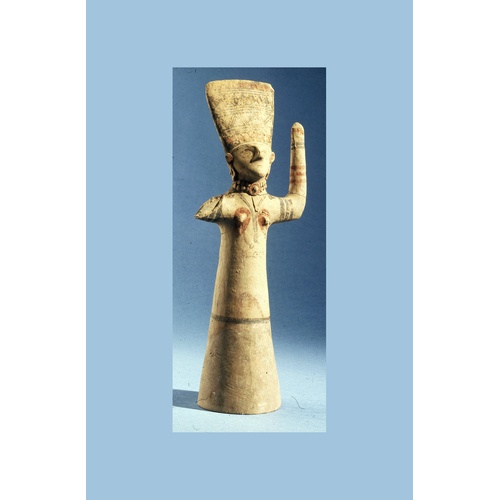

The building or rebuilding of the sanctuaries in the 12th century BC both at Kition and Palaepaphos, with the introduction of horns of consecration and new Mycenaean pottery, as well as numerous other cultural novelties, indicate the presence of Aegean people. Tradition has kept the memory of Greek colonists founding cities in Cyprus on their way back from the Trojan War. The Arcadian Agapenor was said to have founded the temple of Aphrodite in Paphos, but we should bear in mind that a goddess Aphrodite was unknown in Greece in the 12th century BC. Another tradition referred to by Tacitus that mentions Kinyras (probably of oriental origin) as the founder of the temple of Aphrodite in Paphos seems more likely. From what we know about the goddess worshipped in Paphos in later times, her cult had affinities with oriental cults. When the Greeks arrived, they may have adopted the local goddess, identifying her with some female deity they already worshipped, and they gradually hellenised her, favouring the development of a new type of figurine. For it is a fact that a local goddess was represented by figurines of an oriental type in the previous centuries, and that figurines of a new type made their appearance in the 12th-11th centuries BC. The new mixed population may have maintained for centuries some aspects of the cult of the old goddess at Palaepaphos with its oriental institutions (king-priesthood, sacred prostitution, perhaps sacred marriage, oracle, deity represented as a baetyl) inherited from previous oriental religious practices. In the course of the 11th century BC, waves of Aegeans, mainly Cretans, brought to Cyprus new religious elements. Around 1100 BC, another type of figurine appeared, characterized by her uplifted arms pointing to the Cretan prototype of the Minoan Goddess with upraised arms. Figurines of this type are found in the new temples of Kition, rebuilt in the 11th century BC, in sanctuaries in Enkomi, Palaepaphos and elsewhere. The goddess is represented in this type for several centuries. The new type depicts an image of the Lady of the Sanctuary [Fig. 3] with a cylindrical body; her arms are raised in a ritual gesture and she wears an imposing headdress and a long dress. She was no longer seen as a wild goddess of sex, but as a divinity radiating majesty. Her images were offered in her sanctuaries, and were no more deposited in tombs.

Around 900 BC the Phoenicians established a colony at Kition and rebuilt the earlier temples. They dedicated the largest temple to their goddess Astarte who was worshipped at Kition till the 4th century BC. The cult of Astarte had many similarities with the cult of the Cypriote goddess of fertility.

Amathous, which – according to tradition – was founded by indigenous Cypriotes who kept the Eteocypriote language and perhaps very ancient rites, had also developed as an elevated place where the cult of the goddess was venerated, possibly as early as the 11th century BC. A sanctuary dedicated to the goddess existed at the top of the acropolis from the early 7th century BC, and evolved into a great religious centre during the Archaic period. Many archaic female figurines of the nude type with hands on their breasts that were found at the site of the sanctuary and in tombs testify to the worship of the goddess who was more or less identified with Astarte and Hathor. It is mentioned that the goddess in Amathοus was hermaphrodite.

Religious influences from the Syro-Palestinian coast brought in again the image of a goddess represented by naked figurines with hands on their breasts and strong sexual features. This new type of figurine spread particularly during the 8th-6th centuries BC in sanctuaries of the central part of the island, which may have been under the influence of the Phoenicians.

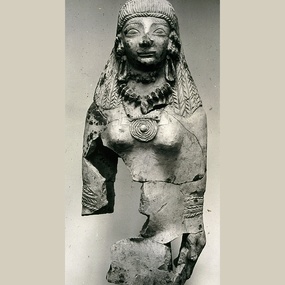

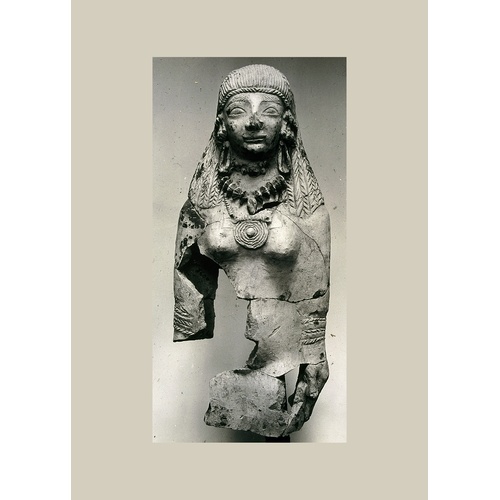

The Cypriotes gradually disliked the sexual appearance of their goddess and from the 6th century BC they represent her as an imposing priestess/goddess [Fig. 4]. Numerous figurines show her fully dressed under heavy garments and wearing rich jewellery, but still with her hands on her breasts. Figurines of her worshippers offering a young animal, a dove, a flower, a cake, a vase, and musicians playing the tambourine, and later the lyre, were also dedicated in her sanctuaries. By the end of the 6th century BC, sculptors had started producing grandiose statues in limestone, representing the goddess or her worshippers.

The Archaic period was probably a time when the goddess was lavishly worshipped in her principal sanctuaries of Palaepaphos and Amathous, but also in numerous rural sanctuaries all over Cyprus. There was an abundance of offerings in the sanctuaries, illustrating the cult of the goddess which probably included ceremonies with the playing of the tambourine and the lyre, incense burning, dancing, giving oracles, offering of doves, young animals, flowers, and vases.

By the end of the 5th century BC, the Cypriotes became conscious of their Greek identity. In the meantime the cult of Aphrodite had developed in Greece. The goddess and her worshippers in Cyprus were now shown in Greek dresses, and with Greek features, but they were still distinct in their lavish ornamentation and rich jewellery. Somewhat later, in the 4th century BC, the goddess was shown wearing a high vegetal crown, symbol of prosperity, or a turreted crown as a protector of cities. She appeared on the coinage of many kingdoms, as the great deity of Cyprus offering protection. By the 4th century BC, she was assimilated with the Greek Aphrodite.

In the Hellenistic period, the temple of Aphrodite at Palaepaphos developed as the main and prestigious cult place of the goddess. Ptolemy Philadelphus associated her cult with the cult of Arsinoe, his sister and spouse. The sacred precinct was kept as it was. The only finds surviving from this period are numerous dedications.

At Amathous the cult of the goddess was kept very vivid as witnessed by the great number of figurines and statues of the Hellenistic period, while her cult was associated with the cult of Isis and Adonis. The ruins, which survive until nowadays and date from the 1st century AD, are those of an imposing temple in the Greek style with a cella and a colonnade, and Nabatean capitals on its façade.

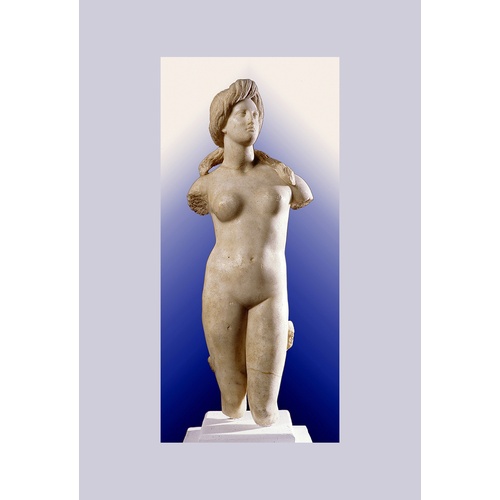

At Soloi, two temples were erected in honour of Aphrodite in the 3rd century BC and were in use till the 4th century AD. There her cult was associated with the cult of the Egyptian Isis. Soloi produced a number of statuettes and statues of Aphrodite, represented as a nude beautiful deity [Fig. 5].

The Romans made the old sanctuary of Palaepaphos a place of pilgrimage, since they considered Aphrodite to be the origin of their race. The precinct was kept as it was, with the conical stone (baetyl) symbolizing the power of the goddess still in place, but annexes were built to shelter pilgrims who came from all over the Mediterranean to worship her and consult her oracle.

In the Roman period, the temples of Paphos and Amathous were places of asylum according to a right granted by the Romans.

The temples were abandoned in the 4th century AD, after repeated earthquakes and the edict of Emperor Theodosius that closed all pagan temples.

The name of the goddess

From the few early inscriptions available (6th century BC), we know that the goddess was simply called η θεά, the Goddess, or the Paphian, or the Golgian (from the name of her two main sanctuaries). In Paphos, in the 4th century BC, she was still called Ἀνασσα, a very old Greek name meaning the Sovereign. She began to be called Aphrodite in Amathous at the end of the 4th century BC as found in royal inscriptions. From then onwards she was invoked as Kypria Aphrodite or Paphian Aphrodite in numerous inscriptions of Hellenistic and Roman times.

Although Homer knew her already as Aphrodite, this name is not recorded in Cyprus in early times. At first sight, this name may be explained with the phrase born from the foam of the sea (αφρός means foam), but not from a linguistic point of view. Linguists rather think that Aphrodite could be the phonetic transcription of an oriental name like Attorit, akin to Astarte, given by the Greeks to the old goddess of Cyprus. The myth of her birth includes elements from very ancient Sumerian and Hittite cosmogonies in which the father god is mutilated by his son. A myth from Byblos, closer to the Cypriote myth, narrates that the god Uranus was mutilated by his son and the blood from his genitals fell into the river of Byblos. The introduction of a maiden born from the foam created by the genital parts of Uranus could be an invention by some Cypriote hymn singer in order to explain the goddess’ name.

Mythology

The rich mythology around Aphrodite may have originated in Cyprus from aspects of her cult at the time when the Greeks adopted this deity. She was a fierce sexual goddess, patroness of copper, and protector of the fertility of nature. Hence she came to be associated with many lovers, Hephaistos, the god of metallurgy, and Adonis, the god of vegetation. Here are some mythological episodes associated with her:

Aphrodite is caught with her lover Ares by her husband Hephaistos and flies to hide in her sanctuary in Paphos (Homer, Odyssey 8.356-366).

Aphrodite prepares in her temple in Paphos to go to meet the Trojan shepherd Anchises with whom she falls in love (Homeric Hymn 5.53-57).

Pygmalion, king of Paphos, is in love with a statue of a beautiful woman he had carved in ivory and Aphrodite gives life to it (Ovid, Metamorphoses 10.242-299).

Aphrodite inspires an incestuous love to Myrrha for her father Kinyras, and she gives birth to Adonis (Ovid, Metamorphoses 10.298-502; Plutarch, Moralia 311).

Aphrodite turned into stone statues the Propoetides of Amathous who denied her divinity (Ovid, Metamorphoses 10.238-242).

It is clear from the above that a local fertility deity played an important part in the religious life of the Cypriotes from a very early period. In the 2nd millennium BC, she was deeply influenced by Near Eastern religions. In the 12th century BC, she was encountered by the Achaean Greeks in Cyprus and acquired Greek characteristics, mixed with Phoenician elements deriving from the Syrian goddess Astarte in the course of time. She was almost completely hellenised in the 4th century BC. Altogether she had been adopted by the Greeks at an early date, and she eventually found her way to Mount Olympus as the goddess of love and beauty.