The Cypriote syllabary: first discoveries and decipherment

The epigraphy of the Cypriote syllabaries counts now more than 200 years since modern rediscovery of the relevant evidence.1 A voyage by Josef von Hammer in 1800 which resulted in the detection of the first Cypriote syllabic inscription, was followed by the publication of the founding volume of the Cypriote epigraphy, Numismatique et inscriptions chypriotes (1852) by the Duke of Luynes. In his monograph, the French collector suggested for the first time the existence of a distinct writing system, unique to Cyprus; he based his observations on coin inscriptions, but, mostly, on the Idalion bronze tablet, found already in 1849.

The retrieval of the first biscript (Greek alphabetic/Cypriote syllabic) in 1862 by the Count Melchior de Vogüé (ICS2 260, Golgoi), was followed by a second (Phoenician alphabetic/Cypriote syllabic) in 1869 by Robert Hamilton Lang (ICS2 220, Idalion). With a paper presented to the Society of Biblical Archaeology in London, R. Hamilton Lang in 1871 dealt with coin inscriptions and contributed to the decipherment with the recognition of the word for ‘king’. He was accompanied by George Smith, a cuneiform expert of the British Museum, who suggested a number of correct sign values based on the transcription of the Phoenician text and hinted that word declensions recalled Greek and Latin, whereas the names seemed Phoenician and Greek. He was assisted by his fellow Egyptologist Samuel Birch.

Johannes Brandis, a Prussian numismatist picked up the task in 1873 by suggesting more sign values, some of which proved to be correct. In 1874, Moriz Schmidt, starting with the assumption that the language recorded was Greek, corrected some false readings. Schmidt’s work culminated in a collection of inscriptions published in 1876,2 which contained all the then known inscriptions, including the ones that had just been discovered by L. Palma di Cesnola. Schmidt did not include coin inscriptions (except for one!) and did not assimilate his colleagues’ contributions to the decipherment. At the same time, two other scholars, Wilhelm Deecke and Justus Siegismund, working independently in Strasburg arrived at more or less the same conclusions (1874), but their work was published slightly later than Schmidt’s. So, what started with the presentation of R. Hamilton Lang in 1871 reached within the following five years a happy outcome, that of the complete decipherment.

Collections of inscriptions and projected corpora

W. Deecke, after Siegismund’s premature death during a visit to Cyprus (1876), was charged with the preparation of the first collection of inscriptions as part of a bigger project on the Greek dialectal inscriptions under the direction of Hermann Collitz and Friedrich Bechtel.3 The inscriptions in the Cypriote dialect inaugurated the series (nos 1-212). The material was divided according to the four Roman regions of the island (“Lapethia”, “Paphia”, “Amathousia” and “Salaminia”) and contained a number of inscriptions now lost. The editor included many coins (nos 151-212), but he missed the publication (in the same year) of Six’s fundamental study on Cypriote coinage.4 Because not much time had elapsed between the decipherment and this publication, and due to the fact that the recording of inscriptions was still at an early stage, the volume soon became dated. In less than 10 years, a new volume by Otto Hoffmann appeared,5 which, along with Deecke’s 1883 volume, remained the standard reference for many of the years to come.

History of research

In the beginning of the 20th century the project of compiling a corpus of Cypriote inscriptions was undertaken by Richard Meister on behalf of the Inscriptiones Graecae project, an assignment that was never materialised. A handwritten catalogue by Howard Slater listed syllabic inscriptions in the Cyprus Museum, apparently during the process of reorganisation of the museum. After half a century of stagnation, Terence B. Mitford’s continuous travels to Cyprus, his excavations and studies from 1936 onwards, resulted in new finds and more in-depth studies on the Cypriote syllabary. The project of a corpus was announced by Mitford in 1952, but it similarly never came to fruition.

The standard reference for all scholars of Cypriote archaeology and epigraphy is to this day, Les inscriptions chypriotes syllabiques, which is not a Corpus but a collection of Cypriote syllabic inscriptions which appeared in 1961 edited by Olivier Masson.

A new projet of Corpus: Problems, methodology

The inscriptions registering Greek and the so-called Eteocypriote languages by means of the Cypriote syllabary, as it was used for most of the 1st millennium BC, are numerous. A database compiled by J.-P. Olivier (with the collaboration of Fr. Vandenabeele on matters of chronology), containing 1,354 entries (that now has risen to 1,397 entries) has been made available to an international core group of three researchers (Italian-Massimo Perna, Greek-Artemis Karnava and German-Markus Egetmeyer), with the assistance of two more, for the time being, researchers (Swedish-Hedvig Enegren, Greek-Evangeline Markou).

An unavoidable problem is the dispersal of Cypriote antiquities (including inscribed pieces) in 34 museums around the world, as a result of antiquities trade. Additionally, ancient Cypriotes, users of this writing system, have not been helpful towards modern researchers: Cypriote mercenaries, hired by Egyptian pharaohs in the 4th century BC, left their written traces on Egyptian temples in Abydos and Karnak. Any prospective researcher realises that this (both ancient and modern) scattering of inscriptions has been the reason why all previous attempts to gather inscriptions under one roof have come to a halt: personal inspection and faithful recording by photographing, drawing and transcribing inscriptions is imperative, in order to minimise the risk of producing false readings of these inscriptions.

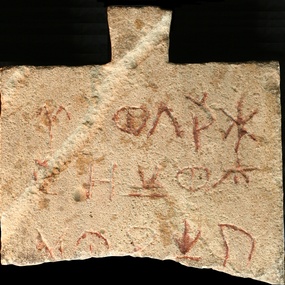

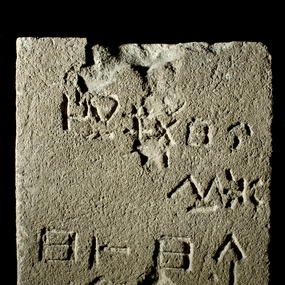

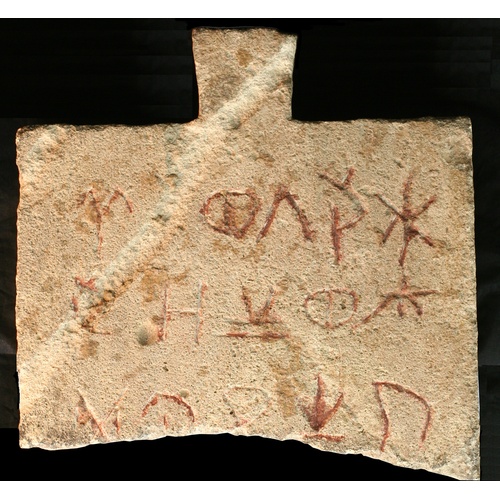

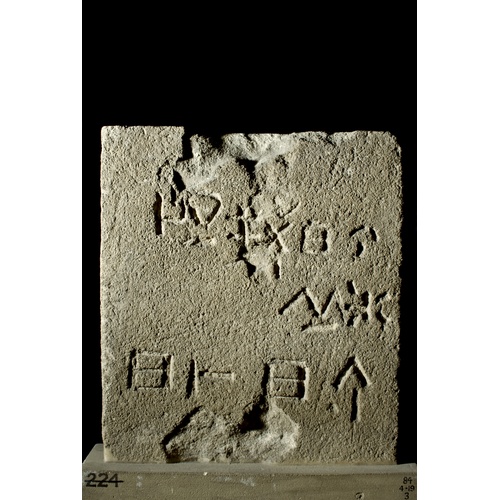

The project uses a methodology developed over the years in the field of Mycenology (the study of Linear B), which is original to the field of Cypriote scripts. An epigraphist needs to start with acquiring the best possible photographic documentation. Photographs are subsequently used to produce drawings of inscriptions; drawings have to be checked against the original inscribed object, to ensure that misinterpretations are minimised. Thus, a correct drawing forms the basis for the transliteration of the inscription in the modern Latin alphabet. In this way, the reading of an ancient inscription is achieved and then handed over to linguists, philologists and historians to use as primary sources of information in their respective fields.

The project has found a publishing home under the well-known Inscriptiones Graecae and will be part of volume XV (Inscriptiones Cypri).

The 1,397 inscriptions are expected to appear in (a minimum of) three fascicules.

As mentioned above, previous efforts with the same objective seem to have failed either due to lack of time (it is an impossible task for one individual to carry out) or travelling funds (the case of the last group which advertised a similar project).

At the moment the proposed division of the material is the following:

Fascicule I. Marion (302), Kourion (43), Amathous (41) = 386 inscriptions.

Fascicule II. Paphos and its area = 464 inscriptions.

Fascicule III. Other sites = 547 inscriptions.

The publication of the inscriptions will be accompanied by the proper concordances and indexes.

Expected results

The main benefit of this project is the study of the Greek language, in the variety that was used in Cyprus (the so-called Arcado-Cypriote dialect). At the same time, the corpus is intended to benefit the study of the writing system on its own right. A writing system is initiated and diffused from the organised authorities of a given territory and the local, poorly studied variations of this script demonstrate complex social and political relations; it is these relations that an in-depth study of the writing system is aimed at highlighting and, ultimately, assisting the production of written history.

The corpus is also aimed at promoting the study of its ancestral scripts. The 2nd millennium BC Cypro-Minoan writing system is thought to be the predecessor of the script which concerns us.

In 2007, an edition of Cypro-Minoan inscriptions was published by J.-P. Olivier. In view of the lack of digraphs, which are of paramount importance to the decipherment of the corpus of inscriptions of the 1st millennium will undoubtedly advance the decipherment perspectives of the Cypro-Minoan writing system.

Balance

So far all the inscriptions from Marion, Kourion and Amathous are photographed and drawn after many research travels to the USA (Metropolitan Museum, Philadelphia Museum), England (British Museum, Fitzwiliam Museum), France (Musée du Louvre and Cabinet des Médailles), Germany (Berlin Museum), Italy, (Museo di Antichità di Torino, Museo Archeologico di Napoli, Museo di Policoro), Greece (Athens Archaeological Museum, Agora Museum, Delphi Museum, Museum of Cycladic Art), Sweden (Medelhavsmuseet), Cyprus (Nicosia Museum, Polis District Museum), Poland (Goluchów Castle).

In 2015, we will finish the correction of the 386 drawings and complete the volume that we will present at the next International Conference on Aegean Scripts in Copenhagen in September 2015, as we announced in Paris in September 2010, at the latest International Conference.

The project is supported by the Institute for Aegean Prehistory of Philadelphia (INSTAP) and the National Hellenic Research Foundation, Institute of Historical Research, Section of Greek and Roman Antiquity (KERA).